|

|

What happened with our hummingbirds in 2007?

The 2006 capture season was a kind of training period: we were learning our work methods; we got the requisite permit in late May and the bands came on June 10. Over the summer, we changed the type of cage we were using and perfected our capture techniques. The 2007 season was a different matter. We were ready and raring to go; we knew our cages worked well and our reflexes were well honed. The results were everything we had hoped for. The period extended from May 6 to August 29. In 2006 - 229 captures In 2007 - 403 captures; 369 new birds, 33 returning birds banded in 2006 and 1 bird banded in Houston, Texas, in 2005. Stoke - 241 birds 228 new * 130 adult males 13 returns * 7 adult males Richmond - 126 birds 106 new * 39 adult males 20 returns * 8 adult males Orford - 32 birds 32 new * 13 adult males Saint-Denis-de-Brompton - 3 birds 2 new * 2 adult males We also got hundreds of data entries from watchers across Québec, which were greatly appreciated. Unfortunately, only two sightings of colour-marked hummingbirds were reported. |

|

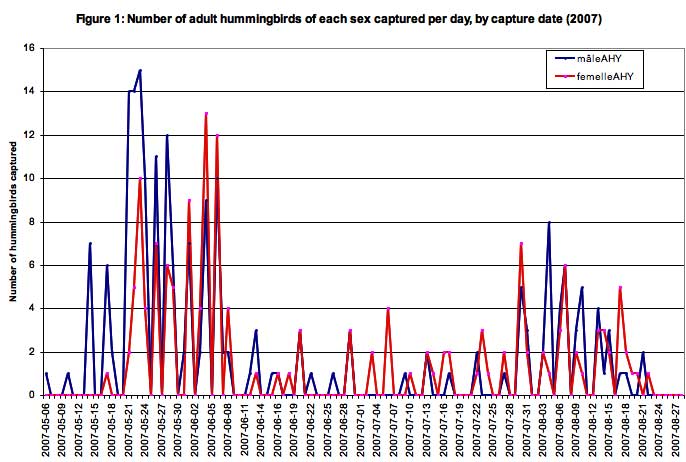

Migration phenology in 2007 One of the main objectives of the Projet colibris to determine the migration phenology of the Ruby-throated hummingbird (Archilochus colubris). By plotting the numbers of hummingbirds captured on each day (weather permitting) from May 6 to August 25, 2007, we can get a good idea of the migration phenology for the Estrie region, for birds of both sexes. It is already known that males of this species migrate earlier than females in spring, and the same is true in the fall. Figure 1 shows that, even at the northern edge of their range, the spring migration phenology of hummingbirds is comparable to the findings of other studies. In fact, we can see from the figure that the peak in male captures is about 7 days ahead of that for females. This confirms that, even though some females are captured early, most of them arrive after the males. However, the results are less clear for the fall migration. On the same figure, we see that female captures remain steady throughout July while the number of males captured shows a marked decline over the same period. We also see that the number of hummingbirds of both sexes captured increases starting in late July, suggesting that the fall migration is well under way. Another observation: the number of hummingbirds captured in the spring is higher than in the fall. There are at least three possible explanations for this finding:

Of course, we can get more detailed knowledge about this by compiling migration tracking results for a number of years, and maybe, one day, by increasing the number of hummingbird banding stations in Québec. |

|

|

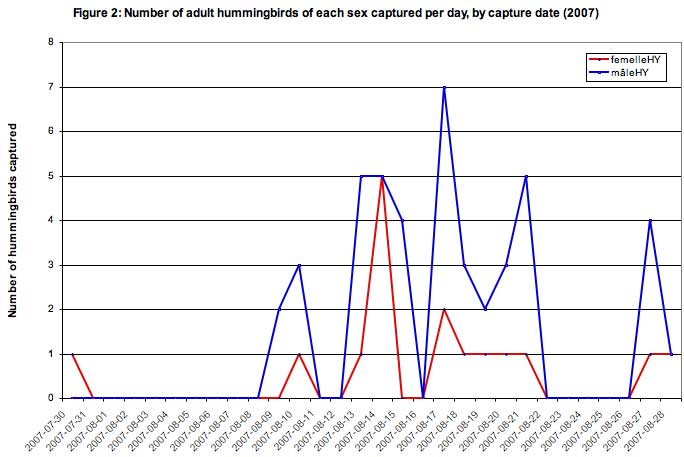

What about the migration of young hummingbirds? In 2007, we captured our first young hummingbird, a female, on July 30. The total number of young females captured was considerably lower than the number of young males (15 vs. 38). From Figure 2, we can see that young females appear to migrate earlier than young males. This result may be due to a potential sex ratio bias towards more young males in the population. Indeed, more young males than young females may be born in our hummingbird populations. This would compensate for the higher mortality rate of adult males, bringing the sex ratio for the population into balance. Also, an effort to keep capturing birds right up to the end of the migration (around September 20) may be needed in order to establish the phenology of the end of the fall migration for young hummingbirds with more certainty. One thing is sure: young hummingbirds are the last to visit our feeders. As data accumulates on various demographic parameters such as sex ratio and recruitment, we will gain a better understanding of differences that may exist in the migration sequence of these wonderful, fascinating tiny beings. |

|